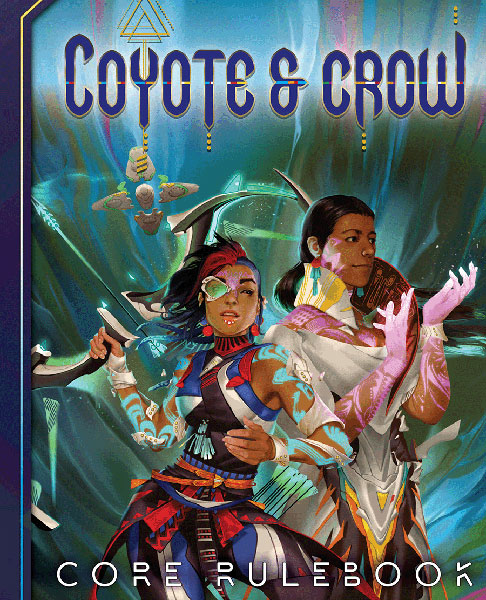

Coyote & Crow Core Rulebook is a role playing game published by Coyote & Crow LLC.

The supplement is available as a 484 page Pay What You Want PDF from DriveThruRPG. It is also available in printed form from sites such as Amazon. The PDF is the version reviewed and two pages are the front and rear covers, two inside cover pages are blank, two the front matter, three the Table of Contents and two the Index.

Section 1: Welcome to Another World starts with Chapter 1: Waya’s Lesson. This is a piece of in-universe fiction, which itself has an in-universe legend woven into it.

Chapter 2: A Message to Players has a couple of messages on playing the game, one to Native American players, one to those who lack such heritage and finally one to all players about how commonly used words that are capitalised have a specific game meaning found in the Game Terms Glossary, and any word that’s unfamiliar is likely Chahi, the fictional trade language created for the game.

Chapter 2: A Message to Players has a couple of messages on playing the game, one to Native American players, one to those who lack such heritage and finally one to all players about how commonly used words that are capitalised have a specific game meaning found in the Game Terms Glossary, and any word that’s unfamiliar is likely Chahi, the fictional trade language created for the game.

Chapter 3: A Brief Introduction to Roleplaying gives an overview of what role playing is, a description of the role of the players and the Story Guide – GameMaster – the use of d12s and the Coyote & Crow app.

Chapter 4: Roleplaying in the World of Coyote & Crow starts by explaining this is a world in which something happened in 1400 AD, which resulted in the Earth suffering a severe climate change for hundreds of years. The Americas were changed, especially as an ice sheet formed, and a strange purple mark called the Adanadi appeared on plants, animals and people, which became a source of inspiration and power. When the ice sheets began to melt, new technologies and trade brought an upswing in the standard of living. There are significant differences between these Americas and European-influenced ones. The calendar starts at The Awis, the 1402 AD event. It explains that this book focuses on Makasing (North America) and specifically the city of Cahokia and the area around it.

Following this are some details on the changed world and how the Adanadi can change those in whom it’s introduced; they permanently change and sometimes have abilities beyond the human norm. With the ice sheets retreating, attempts have been made to explore beyond them, but monsters have made this almost impossible. There is also a map of the continent and a timeline of major historical events.

Chapter 5: Makasing And The World Beyond details the various locations in the setting. It starts with Cahokia, which is covered in the most detail. This is a city, the largest one in Makasing, and within the Free Lands. There is a colour two-page map of Cahokia with some places marked that are named and, very briefly, described. More details on the city, its politics and government, demographics, infrastructure and architecture, food and farming, economy, justice and the law, spirituality and religion, education, science, time, culture, art, music, comedy, poetry, theatre, sports and games and leisure are given. It then covers daily life in Makasing, looking at medicine and health, sex and sexuality, gender, marriage and family, old age and death, life and conception, tribes, paths and day to day living.

Details on other places in the setting are then looked at. The Five Nations are the five nations that cover the northern section of Makasing. Each of the nations is given an introduction, government and politics, economy and technology, society and culture, factions and groups and major cities and locations within the nation.

The Free Lands are considered one of the Five Nations, but don’t fit the same mould. They are given an introduction and a look at the various different peoples found in the region.

The World Beyond Makasing covers, in less detail, the equivalent of Mesoamerica, giving brief overviews of the major nations, and the equivalent of South America in the same manner.

And Even Further… gives overviews of the permanent ice zone, some island people and then even briefer looks at the rest of the world; Hawai’i, Africa, Asia, Australia and Europe. Little is known of most of these places.

Chapter 6: Languages and Communication gives an overview and history of the languages used in the setting. There are almost 250 languages, with Chahi being the closest thing to a common tongue; the name means “The Mix” and it is a blending of different languages. It is also a language created for the game and some features of it are covered, though it is gone into more detail on the publisher’s website. The sign language of the Plains tribes is looked at, as well as the written language that evolved from Azayang inscriptions are also covered briefly.

Chapter 7: The Adanadi discusses the purple mark that started appearing after The Awis. When these marks initially appeared, they were thought to be everything from blesses to plagues to curses. When biology and chemistry advanced enough, the secrets of the purple marks started being understood; it was a mutation caused by a non-terrestrial form of life. Injecting it into the brain stem of a human during adolescence could grant them powers and abilities, and there are other uses for the Adanadi. The abilities of those who gain power from the Adanadi is looked at, and how such abilities are used.

Chapter 8: Technology starts by giving an overview for how technology has developed in the setting; the primary difference is that many technological items are manufactured by 3D printing, then customised for an individual, rather than being mass produced. Solar and wind power are examined, then yutsu lift technology, which powers most vehicles and is based on the Adanadi. Second Eyes are goggles that can act as an information source as well as having an augmented reality ability. Gats are 3D printers which can turn lots of stuff, often such as food waste, into items. Niisi are personal computers worn on the forearm, and are used to communicate. Communications across national borders are tightly controlled by the governments. There is an equivalent to the internet, the daso, though it has differences. Space travel does not exist as such as yet. There’s also a note on technology that doesn’t exist but which could. The final part of the chapter is a story.

Section 2: Crafting Your Hero starts with Chapter 9: Characters. There’s an overview of the 14-step process – with some sub-steps – for creating the character; quite a large number of steps, though some are small. Motivations are what drive the character, and an optional rule can give a penalty if characters are going against it. There is a list of sample Motivations. Archetypes are a combination of careers, personality, jobs and motivations. There are six Archetypes, Warrior, Scout, Tinkerer, Seeker, Healer and Whisperer, with examples of their roles. Other identifiers have no game mechanic but are part of a character’s identity.

Paths are a one-time choice that represents the type of ceremony they go through on reaching adulthood; they are important and are locked in once Adanadi are received. Fifteen Paths are listed with their related Stats. Character Points come in three types and are spent on Gifts and Burdens, Stats and Skills and Skill Ranks. Gifts and Burdens are the unique challenges, features and resources of characters. Taking Burdens grants points that can be spent on Gifts; the more points spent on something, the more game effect it has. Various Gifts and Burdens are covered and how they affect things.

Stats range from a low of 1 to a high of 5. They are divided into three categories; Physical, Mental and Spiritual. Each category has three Stats. The first Stat in each category represents raw Power; these are Strength, Intelligence and Spirit. The second represents Finesse; these are Agility, Perception and Charisma. The third represents Reserves; these are Endurance, Wisdom and Will. How the Stats are generated, and what each means is then covered.

Skills are, well, skills. They come in two types; General and Specialised. Specialised Skills are subsets of General Skills; the General Skill must be possessed to have a Specialised Skill. How Skills are bought in character creation is covered, and there’s a list of the General Skills with the two related Stats. The Skills are then described, with the Specialised Skills explained following a General Skill’s description.

Abilities are the superhuman powers gained when an Adanadi Path was chosen. The Abilities are divided into nine categories based on Stats and there’s a table with the name of each ability – there are three per Stat – and a short description. Longer descriptions cover the Ability in more detail, with how they are activated, the dice check and what the ability does.

The sort of equipment a character starts with is covered, followed by the Derived Stats, which are based on the main Stats. These are Imitative Score, Physical, Mental and Mystical Defence and Body, Mind and Soul.

The final step is determining the character’s background.

Chapter 10: Equipment covers, as it suggests, the various kinds of equipment. It starts with currency, the nizi, which was originally intended to represent one hour of labour, though modern economics have changed things a bit. Though economies vary from state to state, most have government run businesses that supply food, shelter, power, education and health care. Gats are similar to 3D printers, though more common and widespread than current ones. Additional assembly may still be required for gat-printed items.

Items have Cost Ranks between 1 and 8, rather than a nizi cost. This is an abstract cost used when making Wealth Checks which are based on a character’s Wealth Rank. Characters can also take on debt. Wealth Checks should only be made when there’s a need to; items below their Cost Rank can easily be bought within reason, but at their Wealth Rank and above is a different story.

Following this are some details on the terminology used in describing gear. The rest of the chapter is then taken up by descriptions of this, divided into clothing and armour, technology, kits, drugs, poisons, weapons, both melee and ranged, vehicles and drones and cybernetics.

Chapter 11: Goals and Progress looks at Short-Term Goals, Long-Term Goals and Group Goals. Characters may pursue up to two Short-Term Goals at any time, which are things such as improving or gaining a skill or obtaining a piece of equipment without a Wealth Check. Long-Term Goals can be such as gaining a new Ability, increasing a Stat, gaining a new Gift, increasing the Level of a current Gift or decreasing the Level of a current Burden. How these are done and the time they take – in Sessions – are covered. Motivations can also be changed. The Story Guide will also have a Goal for the whole group, which is typically the natural co0nclusion to a Stroy, set of Stories or Sage, and isn’t spelled out to the players. Finally, characters can also retire when they become legendary enough that things are no longer as challenging.

Section 3: Rules of the Game starts with Chapter 12: The D12 System and the chapter begins with the dice rolls known as Checks. There is an overview of how a check is done, including optional steps, before explaining in more detail. Coyote & Crow uses Dice Pools; most require standard white dice (or whatever is being used as such) and the number of dice in a pool is normally determined by whether Abilities, Skills or Stats are appropriate. The Success Number is determined, with 8 or higher on a die representing a Success as a default, though other factors can change this. Legendary Ranks allow die results to be adjusted up or down by 1 point; each rank allows 1 point in movement and multiple points can be added to one die. Focus allows something similar by spending points from Mind on any die that is not a Fail. Critical Dice are rolled for any 12s that are natural or adjusted to that by Legendary Status or Focus. One or more Successes is success, 0 is Failure and below 0 is Critical Failure. The process looks more complex than it is and is similar to how many dice pool systems work, just using d12s. Characters may also make Skill Checks Over Time, where more time is spent, for appropriate checks, to improve the chances of success. Finally, it looks at inventing things and how to handle this.

Chapter 13: Playing Coyote & Crow explains that this section will cover the specifics of a Session. There are two types of play; Encounters and Narrative. Encounters take the longest to play but take the least amount of in-universe time. Narrative Play is where a scene is described and players decide what their characters are doing. This generally doesn’t involve Dice Checks, but can do; if the GM decides the narrated play needs a dice check, one is made.

Encounters are looked at next, and are defined as being the systematic taking of actions by characters over a series of rounds. Unsurprisingly, this often means combat. Rounds and the various types of actions that can be done in Encounters are covered; though actions in combat may be called different things or work slightly differently, they are comparable to most other games of a similar level of complexity. Combat is not the only type of Encounter; there are also social, contested skill checks, player vs player, asymmetrical and spiritual. Following this it looks at encounters involving vehicles, animals and pets, machines and robots, inanimate objects and spirits and gods, finally looking at the place known as The Black, which isn’t fully understood.

Chapter 14: Damage, Death and Healing looks at what Damage is, the different types, the effects, how to inflict it and how to take it. It starts by recapping concepts from earlier in the book before moving onto the Damage types. Physical Damage is represented by Body and represents physical resilience. Reducing it to zero risks unconscious; below that and the character begins dying. Physical Damage has subtypes of fire, cold, electrical, falling, non-lethal, mental and spiritual. Fortitude represents strength of character. Following this, it looks at Damage that can take place over multiple rounds, this being environmental, poison, bleeding, stun and burning.

States are the states a character could be in. Conscious is the default, but there are also sleeping, altered, panic and unconsciousness. Some attacks may also cause Stat Damage, which affects the characters Stats and which heals more slowly than traditional Damage. Dying is the process that starts when a character has less than zero points of Body, Mind or Soul. Each round, the character will need to make rolls to see if they can be stabilised, and other characters can affect this. Death is a big event and the Dying process is a long road to death. Also, a character doesn’t die unless their player agrees to it. Which does remove any bit of worry about death and pretty much makes the dying process totally irrelevant, as well as anything else with an element of chance, because no matter what happens, the player can refuse to let their character die. Instant death is an option, but again, this is overridden by the player refusing to have their character die. It’s said that this rule can be overridden, and frankly it should be in order to stop players from abusing it. Finally, it looks at healing, the effect of short and long rests and how to heal Stat Damage.

Section 4: For the Story Guide starts with Chapter 15: Getting Started. This begins by explaining the job of the Story Guide; anyone familiar with being a GM will already know this sort of thing. For those that don’t, it covers getting a game started and consent. The next section covers the various terms used in Story Guiding and explains them in detail. Again, there is nothing much new here, even if the terminology used is slightly different. Finally, it looks at concepts that aren’t game terms but which are important. There is the default setting for the game, themes that the game can contain and the tone of the games, which could cover anything from action to comedy to horror.

Chapter 16: Forging Your Saga explains that it is a good idea to have some notion of what kind of Saga is going to be played. It then covers the advantages of having the initial stories being about a team of Suyata, as covered earlier, with the starting equipment, setting, themes, tone and three sample Story prompts (adventure hooks). The same treatment is then given to the genres of protection, exploration, espionage, war and horror, though without the starting equipment.

Chapter 17: The Three Path Concept explains that it’s important for characters to be able to make meaningful choices. As such, Three Paths are used for writing Stories, which involves identifying the major decision points and making sure there are three possible approaches to each and outcomes for these. Needless to say, this adds a lot of complexity to designing adventures, especially longer ones, and it would be far better for the GM to just follow the normal process of adapting on the fly to players’ actions, especially as anyone who has ever dealt with players will know that if there are three optional paths, there is a good chance they will choose paths four, five or six. Two examples are given, with three options for each.

Chapter 18: Interpreting the Rules explains that this section goes beyond the letter of the rules so that a Story Guide will be better equipped to deal with things when they have to make their own interpretations of the rules. It starts by looking at how to create your own Gifts and Burdens, working with a player to design them whilst being cautious that they aren’t unbalancing. It then looks at various Skills and how they are used, then doing a more in-depth look at some of the more complex abilities. It then gives a brief look at Encounters, before moving onto science, spirituality and magic; magic is not codified in the game as existing, but it’s also not codified as not existing. It then looks at Legends and Legendary Ranks and the effect these have before finishing with the ethos of the system, which has no mechanics for moral or ethical values. A sidebar looks at some inspirational reading.

Chapter 19: Icons and Legends is essentially the bestiary and starts by explaining the entries. Apart from humans and animals, none of the things described canonically exist in the setting; it’s up to the individual GM. There are three main types. Legends are just given a description and lack stats and abilities. Icons are specific beings with a unique set of characteristics. Fifth Worlders have stats, but represent average humans and animals. Many beings have multiple names but each is given a single Chahi name and a rough English translation. The beings also have four main types; human, animal, creature and spirit. Each also has a Skill Check to see if a character knows anything about the being. The various entries start with people, then animals, then have the rest in alphabetical order.

Chapter 20: Encounter at Station 54 is an introductory adventure that comes with pre-generated characters.

Chapter 21: Final Notes has some notes from the designers.

The Glossary is divided into two sections, one being a Chahi to English glossary, the other being a glossary of game terms.

The final two pages of content are the character sheet.

Coyote & Crow Core Rulebook in Review

The PDF is bookmarked, but not as deeply as it could be. The Table of Contents is to a similar level of depth and is hyperlinked. The Index is not that thorough. Navigation could be better, given the book’s size. The text maintains a two-column format and appeared to be free of errors. There are a variety of custom colour, black and white and line illustrations, up to full page in size, often in styles that are not really complimentary. Presentation is okay.

The first thing to note is that this game is not as big as its page count might suggest; the font used is comparatively large. This means it’s a shorter read than might be expected. The setting in question is an Americas, focusing on the North American continent, that never experienced European colonisation thanks to a disaster. It’s not made clear – deliberately so – whether or not this is a world in which magic works; there are things that might seem magical but whether they are or not is up to the GM. The Final Notes at the end discuss how the alternative future was created; probably, like every other attempt to do that, it is totally wrong, especially given the influence of the Awis, but the alternative is interesting.

Some of the rules seem a little on the clunky side; it’s not the worst game by far, but not the best either, and there are areas where compromises over the type of game seem to have had a bad effect; the previously mentioned ability of players to refuse to allow their characters to die, no matter what the rolls say, does make a lot of rolls and mechanics rather meaningless. Rather like playing a video game in God Mode.

There are completely different feels to parts of the game, which is good, as it is supposed to be a game that is different. So, on that level, it succeeds. It would have been helpful to have had a list of other material that could have been used as reference to learn more. Some of the organisation of the chapters also feels like it could have been better, but there is always a problem with chapter organisation when having the rules and setting in one book. The setting isn’t covered in a huge amount of detail, but there’s a decent amount for starting a campaign in the main city. Coyote & Crow Core Rulebook can be found by clicking here.

Leave a Reply